In this, Part 2, a single report will be examined and commentary provided to shed light on the meaning behind some of the standard vocabulary and concepts associated with health equity. In this way, it may be possible to prevent foreseeable consequences and recognize similar words and maneuvers in other settings.

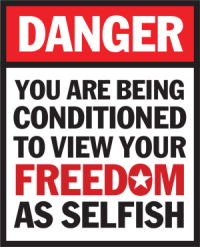

If we are to understand what any of our South Carolina sectors will look like in the future, the best way is to read the reports issued by the state offices responsible for those sectors. Aside from the volume of information, the greatest roadblock is that the words may be unintentionally or intentionally vague or even misleading, concealing truths that could incite citizens against, for example, progressive and globalist forces mandating transformation of their social and political systems as part of a social justice objective.

SC DPH “Health Equity” Reporting

In the matter of our state’s health care system, among the reports worth reading are those issued by the SC DPH in collaboration with the Alliance for a Healthier South Carolina (AHSC). Working together, they developed a separate entity, Live Healthy South Carolina (LHSC), to showcase health studies and health guidance. A handful of reports that guide state health care have been issued through LHSC since 2018. In 2023, SC DPH (then DHEC) announced its second State Health Assessment (SHA) prepared by SC DPH (then DHEC), AHSC, and contributors but released under the LHSC brand. It was followed by a Companion Report.

The 2023 SHA was described as the basis for shaping South Carolina’s future health sector and so it is worthy of closer examination. Specifically, the 2023 report will “provide the scientific foundation to create the State Health Improvement Plan, a roadmap for improving SC population health over the next five years” and is “designed to inform health improvement plans at the state and community levels.” According to the Companion Report:

This document highlights information presented in SC’s second SHA, which was completed in December 2023. …The SHA will be used to create SC’s second State Health Improvement Plan (SHIP) for healthcare professionals, government agencies, communities, and others to use as a roadmap to improve health across the state. The SHIP identifies health priorities to be addressed over five years.

SC DPH Provided Leadership for the Report

According to the full report, “[i]n 2023, DHEC executives served as advisers on the Live Healthy South Carolina Executive Advisory Committee providing leadership, support, and oversight for the state health assessment framework.” Included in the document is a letter, signed by Edward Simmer, nominated by Governor Henry McMaster to oversee the newly restructured SC DPH. Also among the several signatures is Simmer’s now Chief of Staff Karla Buru along with McMaster’s nominee to lead the Department of Environmental Services (DES), interim head Myra Reece. (An organizational chart dated October 2024 was obtained from the SC DPH website.) Executives from AHSC were also signatories.

The full report, is over 400 pages long and contains a great deal of useful information. For the purposes of this article, the focus will be on the section titled “Health Equity.” The purpose is to examine some of the language and to better understand the meaning and potential consequences of the words and concepts relating to health equity. Because the text is not always explicit and may be open to interpretation, it should be considered only this author’s observations, based on years of reading topics relating to critical social justice and equity, including health equity. Perhaps readers will find it offers potential insight into the planned health care agenda currently being rolled out. In no way is the purpose to deny that social factors influence health or to minimize the fact that many find themselves at the bottom of society’s economic ladder. These are real concerns, but they do not warrant a reordering of free society along a socialist and Marxian-inspired framework. And they are currently being addressed at reasonable levels by government, in partnership with a vast and generous collection of organizations and individuals dedicated to helping the less fortunate. The purpose here is to explore and potentially expose elements that may be associated with an insidious effort to transform American society, in part through our health care system.

What is Health Equity?

Tucked among the copious demographic information and colorful graphics is a very important question: “What is Health Equity?” In that section of the report, health equity is defined as “the fair and just opportunity to attain the highest level of health for all people, regardless of race, ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status, geography, preferred language, or other factors that affect access to care and health outcomes.” The awkward wording detracts from a crucial point, being the words “fair and just.” Most people might skip past, not understanding that those words indicate a very special definition of how proponents of health equity view the matter and how that viewpoint skews the terms under which the system may be structured, what its priorities will be, and under what parameters different populations of citizens will receive resources. The repeated emphasis on immutable identity characteristics, often accompanied by emphatic declarations that equity assures a “fair share” for “ALL,” is an indicator of a social justice agenda rooted in Marxian identity politics.

The text specifies at least two “goals,” one for health equity and another for justice. We learn that “the goal of health equity is to adjust treatment, care, and resources based on circumstances and needs….” (emphasis mine) From this we may surmise that health care will be “adjust[ed],” seemingly a reference to quantity and/or quality of access and resources, “based on circumstances and needs” and not based on principles of equality of access to “treatment, care, and resources.” That statement, together with the earlier recitation of immutable characteristics, may signal that populations identified according to these identity markers may receive preference and priority consideration in matters of health under South Carolina’s health equity approach. It should be viewed as bringing those from the “margin” to the “center” where political and social power are described as residing. This also reflects the standard position in Marxian-based ideology which elevates the “marginalized” and the poor to the highest placement for resource allocation.

At the root of equity, no matter the type of equity (educational equity, disability equity, gender equity, digital equity, etc.), the goal is usually expressed as the intention to make all outcomes equal. Equalizing outcomes, for example across sex, financial status, or race, etc., is the cornerstone of socialism and communism and is not a feature of a capitalist system of equality of opportunity. It is, in fact, in opposition to western values. Returning to the document, the very next sentence identifies the second goal: “the goal of justice is to dismantle barriers such as discrimination and lack of resources that lead to inequality and inequity.” From this, a reader might conclude that health equity includes a “justice” component that will entail battling injustice and discrimination by “dismantl[ing] barriers.” This wording may seem unusual to the average person, considering that this document is purportedly outlining state health care policy. But it does seem to support suspicions that this is a social justice health care policy. The “barriers” that will be dismantled may be assumed to be existing policies, practices, and even social values and norms. It would likely involve a form of restitution for past injustices or counterbalancing and overcompensation for perceived ongoing discrimination. This is observable in discriminatory DEI policies dedicated to replacing one population of employees and board members with other identity group populations or offering advantages to one party over another based on race or other identity factor.

The social justice agenda is again underscored here: “Achieving health equity requires valuing everyone equally, with focused and ongoing societal efforts to address avoidable inequalities due to past and present injustices, and eliminating health and health care disparities.” It might appear from this remark that, while we are all equal, some are considered more equal than others, requiring special considerations. One might conclude from the rest of the quote that parties who have suffered in the past or are suffering now from “injustices” must be the focus of efforts to eliminate disparities.

Repeat after me: Equity is “fair and just”

Whereas health equity is described as “fair and just,” the document is careful to contrast it with health equality, seemingly suggesting that equality represents a failure to account “for systemic, historical, and current inequities.” Many might come away believing that “equality” also represents unfairness but could also potentially imply support for a system and a history that allegedly continues to result in current practices rooted in discrimination. Some may conclude that sounds a lot like a politically progressive, social justice framing about systemic injustice or possibly systemic racism. If that proved true, then the reason for queuing up a list of racial identity considerations and socioeconomic class designations could be meaningful factors for future potential access to health care resources. It is common to find these identity and class labels as standard focal points for arguments elevating “marginalized” populations as part of social justice agendas intended to transform systems. Those cases almost always draw on Marxian critical theory, especially critical race theory or its tenets, to pit the “privileged” against the “oppressed” as a method of intentional agitation in order to spur social and policy change.

If you’re wondering about the link between health equity and “climate change” alluded to in Part 1 of this article series, the document takes us there without using the term “climate change,” again raising the matter of fairness and justice. The report further expands our understanding of equity and justice in the context of both environmental equity and health equity in the paragraph titled “Equity, Justice, and the Environment, saying:

Equity and justice also refer to the fair and just opportunity to live, learn, work, and play in a healthy environment. An unhealthy environment due to higher levels of pollution, flooding, or other hazards can lead to poorer health outcomes such as increased asthma or infection. Environmental equity ensures that individuals or communities receive the assistance they need to deal with environmental hazards, natural disasters like hurricanes and disease outbreaks, or human-made events such as pollution, regardless of race, color, national origin, or income. Environmental justice is the removal of systemic barriers and environmental inequities by addressing the root cause(s). (bold emphasis added)

It appears that health equity, according to SC DPH as the responsible office, may be defining the responsibility of government to eliminate disparities in living conditions, attributed to both man-made pollution and environmental disasters. Again, this is framed to be a matter of justice, rectifying past wrongs, and fulfilling obligations that societies presumably owe, perhaps even as a quasi-legal right purportedly held by certain populations. The reference to “environmental justice” together with “flooding” and “natural disasters like hurricanes” suggests that South Carolina’s health policies will include equity considerations relating to “climate change” but that there is a political reluctance to say those words. Environmental equity requires that one part of society picks up the expenses relating to “climate change” and pollution for another segment of society. And readers should be aware that a handful of South Carolina governmental offices are actively pursuing climate change policy implementation and environmental justice initiatives, the subject for another time.

The document appears to suggest that people possess a social right to be provided by government with a “healthy environment” as a matter of “equity and justice.” The implication is that it is right that extends to every environment in which people “live, learn, work, and play.” This is the same kind of argument used by progressives and socialists who claim a citizen has a “right” to government- or society-provided housing, food, employment, transportation, and health care. In fact, the paper will soon move on to suggest those are part of health equity, even if they are not currently legal rights. The arguments are made subtly in sections of the paper relating to SDoH and disparities.

What is the Social Vulnerability Index (SVI)?

Bringing in the “science,” the paper introduces readers to the Social Vulnerability Index (SVI), “a scale that ranks 16 factors related to the socioeconomic status, household characteristics, racial and ethnic minority status, and housing type and transportation of each census tract in the United States.”

The SVI is basically a point system calculated to determine the degree of “health disparities and health inequities” between and among various locations and, by extension, their population demographics. According to the report:

The SVI is based on a ranking of 16 socioeconomic and demographic factors that are grouped into four main themes: socioeconomic status, household characteristics, racial and ethnic minority status, and housing type and transportation. Each census tract receives a ranking for each of the four themes as well as an overall ranking. Areas with higher SVI scores are considered more socially vulnerable and may require additional support and resources during public health emergencies to ensure equitable access to health care and other services.

The SVI is also used in South Carolina’s climate change and “resiliency” planning disaster-recovery documents. The SVI is positioned as a scientific-based reference point used to make vulnerability “official” as a yardstick that will likely be unquestioned when it is routinely employed to describe and prioritize equity-based resource distribution.

It brings to mind the Marxism-based intersectionality, where victimhood points are accumulated based on overlapping oppression characteristics. SVI will rank areas and populations according to their vulnerability score in order to determine resource allocation. Imagine the competition among lobbyists representing organizations and identity groups striving to be considered the “most vulnerable” in order to obtain the greatest shares of “equitably distributed” resources. Those not included in the vulnerable category will be footing the bill for this impossible battle to eliminate disparities. And system incentivized to excel at vulnerability is not a system focused on excellence.

Part 1 introduced the matter of social determinants of health and disparities and sections of this report are worth reading wherever it delves into the individual determinants. The paper’s objective is to offer a kind of emotion-based or moral justification for drawing various economic sectors under the influence of the health umbrella. This sets the stage for a development of interlinked policies and procedures so that, just in time for the next pandemic, natural disaster, or government-declared state of emergency, a chain of policies and regulations can more seamlessly flow through the state system like so many falling dominoes.

Access Part 1 here.

The post SC Health Equity Agenda Exposed appeared first on Palmetto State Watch Foundation.